|

2.3.1 Stages of Cognitive Development |

||

|

The two drawings in Figure 1 illustrate the change in a boy’s drawings of himself between ages 6 and 11. When we look at the way in which children’s drawings change from an early scribble to the intricate drawings of the adolescent, we are seeing an expression of the many cognitive changes which children experience as they mature.

The drawings you have collected will have some similarities because the learners in your class group should be within a year or two of each other. (If you have a wide age range in your class, though, the differences you see may be much greater). Piaget carefully watched his own children’s cognitive development, and then worked on a series of tasks which were done with children of various ages in order to look at the differences between them. We will not look at the tasks at this point, but rather consider the four basic stages identified by Piaget after many years of gathering information about children’s development. However, before we look at the developmental stages, we need to make links with some of the terms we discussed in the introduction to Piaget's theory. You will remember the terms ‘assimilation’, ‘accommodation’ and ‘equilibration’. These refer to a feature of cognitive organisation which Piaget called the ‘functions’. He believes that these functions remain the same throughout the child’s development – that these are the ways in which the human adapts to the environment. You will also remember that we referred to the term ‘schema’. These schemas form the basis of the cognitive structures – and it is these that change as the child matures. Piaget believed that cognitive development was an ongoing process of organisation and reorganisation of structures and schemas. As long as we are faced with new situations and experiences in our lives, we will need to continually organise and adapt our existing schemas to make room for this new information. People are involved in a life-long process of cognitive development. Obviously, the content of thought does differ with age. A child has fewer and more simple schemas in its early stages of life. As a child gets older, s/he develops more and more schemas and these become ever more expanded and complex. Piaget noticed that in certain age ranges, children’s thinking changes quite substantially, because of the reorganisation and expanding of understanding that occurs in their natural development. Piaget believed that the structure of a child’s schemas undergo systematic change at particular points in development. Piaget thus chose to break up the course of development into four stages, which we will now explore. These stages reflect the changes in the type of schemas available as a child develops and the way these schemas are organised into cognitive structures. According to Piaget, the rate at which an individual progresses through these stages is variable, but the sequence of the stages is the same for all children. Piaget Piaget recognised that learners don’t all learn at the same rate or the same pace. What implications does this belief have for teachers in the classroom? All learning and teaching, therefore, needs to be flexible and learner-centred. This means that the learners dictate the pace and rate of their own learning. Teachers, then, need to provide learners with the appropriate (suitable) time and the appropriate (suitable) support (dictated to by the individual needs of the learner), so that the learner’s individual potential can be fulfilled at their own pace. 1. The Sensorimotor Stage (0 – 2years) From the title of this stage – the sensorimotor stage – we can work out that this stage in a child’s development involves two important developmental processes at this time:

The child begins to form simple schemas involving his/her senses and exploratory movement. You will have seen babies exploring the world by touching objects, smelling them and trying to put them into their mouths. This is their way of making sense of their world at this stage of cognitive development, and should therefore be encouraged. Characteristics of this stage include:

2. The preoperational stage (2 – 7 years) Characteristics of this stage include:

If you were then to carefully pour the contents

of one of these glasses into a taller, thinner glass, while the

child is watching, and then ask him/her which of the glasses now

contains more cold drink, s/he would most likely respond that the

taller, thinner glass had more cold drink in than the other.

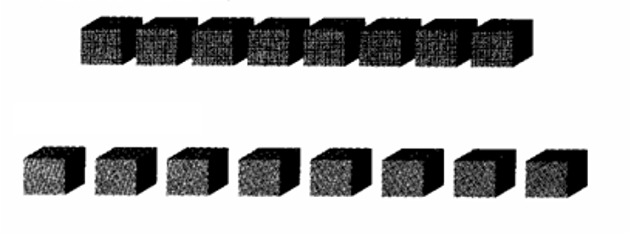

Similarly, we would find that a pre-operational child presented with the situation illustrated above, would believe that there is a different quantity of sweets in the two rows. The child would think that the longer, more widely spaced row of sweets has more sweets than the shorter more closely spaced row. This perception would occur even if the child could see that the same sweets were being moved from one grouping to the other. 3. The concrete operations stage (7-12 years) Characteristics of this stage include:

4. The formal operations stage (13 years onward) Characteristics of this stage include:

We do not study theorists because we believe that their theories and ideas are ‘gospel’, to be followed unquestioning, rigidly and absolutely. Remember that theories act as guides. We need to look carefully and critically at them and see them as merely ways in which we could better understand our learners, and as offering suggestions for our teaching practices. We must be prepared to use Piaget’s theory of stages flexibly, and not expect sudden, clear-cut changes in cognition to occur at predetermined ages. |